Particulates matter: Controlling Dust at Transfer Points

Understanding material flow is vital to controlling fugitive dust to reduce health risks, environmental issues, expensive clean-ups and unplanned downtime. Addressing the root causes may be simpler than you think, writes Todd Swinderman of Martin Engineering.

The root causes of fugitive dust at transfer points are usually obvious but rarely addressed. The common approach to dealing with spillage, leakage and carryback seems to be to treat the symptoms with guesswork. Yet fixing these issues with workable, long-term solutions is proven to increase uptime, reduce costs, improve housekeeping, and ultimately boost profitability.

Reducing visible nuisance dust emissions from conveyors is perhaps understandably a primary goal for operators. Yet it’s the respirable dust that can’t be seen by the naked eye that’s more likely to be responsible for longer-term health issues.

In enclosed operations, the use of respirators is sometimes seen as an acceptable alternative, but PPE should always be a last resort. And besides, respirators themselves can actually reduce productivity, so a more sophisticated root-cause approach to containing dust must be taken.

Settling at Transfer Points

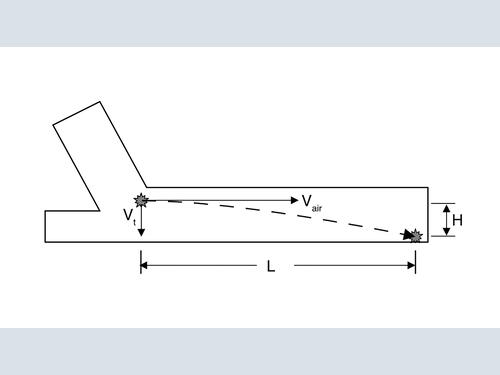

Once material has dropped from a chute or hopper onto on a moving conveyor belt, the skirtboard enclosure essentially creates a settling chamber. The basic concept is that dust particles will settle out of an air stream based on the speed of the air flow, Vair, and the terminal velocity, Vt, of the dust particle. [Figure 1]

There are many traditional ‘rules of thumb’ for calculating skirtboard sizing and dust curtain placement in an attempt to contain the dust in the enclosure. Decades of field experience suggests most of these practices are without proof of performance.

Nevertheless, current practice for conveyor skirtboard enclosures is to design for Vair ≤ 1.0 m/s by increasing the height of the enclosure. A common approach is for the enclosure length to be twice the belt width or 0.6 m for every 1.0 m/s in belt speed. If the enclosure height (H) is increased, the distance (L) that ‘average’ dust particles travel also increases.

Modeling Air Flow

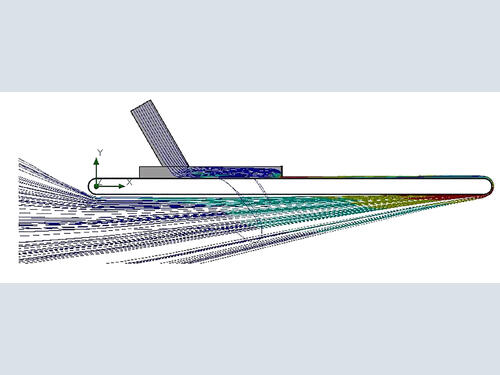

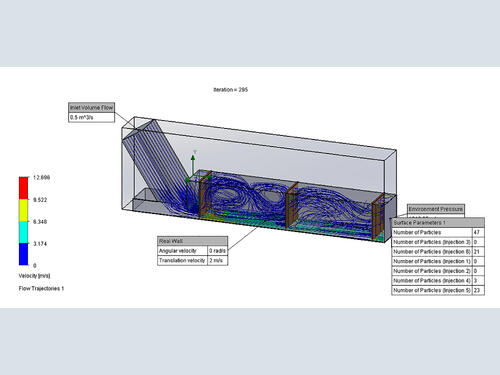

To examine this practice, detailed design studies of air flow and particulate settling were performed by Martin Engineering using flow simulation software. A complete ‘typical’ conveyor transfer point was carefully modeled with a focus on the flow of air in the enclosure of the receiving belt, with both external and internal air flow analysed.

The results of the external analysis indicated that escaped dust particles increased in speed as the air current is affected by traveling around the belt and the discharge pulley. [See Figure 2.] This phenomenon is known as the Magnus Effect and emphasizes the need for effective belt cleaning as close to any discharge as possible.

For the internal analysis, multiple curtain configurations and skirtboard placements were modeled, including some unconventional enclosure designs, to observe dust movement and settling. The optimum design for the standard conveyor was determined to be a conventional enclosure with a height of 600 mm a length of 3.6 metres and three dust curtains placed in defined locations. [See Figure 3.]

The use of a single curtain right at the exit proved problematic in all cases, acting to speed up the exit air flow. This was exacerbated when the curtain was placed close to the belt, re-entraining dust in the exiting air stream, while failing to encourage recirculation within the enclosure. A worn curtain performed as if there was no curtain at all and a curtain coming into contact with the material created the ‘popcorn effect’, where the curtain flicks material off the belt.

Results and Recommendations

The study revealed some useful results relating to transfer point design and a series of recommendations emerged from the research. Here’s a high-level summary:

• Discharge chute width should be >200 mm less than the width between skirtboards.

• Free belt edge outside skirtboard should be more than 115 mm per side.[1]

• Skirtboard height should be > 600 mm.

• Inlet to skirtboards air volume flow should be less than 0.50 m3/s.

• Skirtboard length should be >3600 mm plus allowance for loading turbulence.

• Use at least 3 dust curtains:

o Entrance curtain (1st) at 300 mm past end of allowance for material turbulence.

o Middle curtain (2nd) centered between entrance and exit curtains.

o Exit curtain (3rd) at 300 mm from end of skirtboards.

o Curtain clearance above material: 25 mm preferred, 50 mm max.

o Curtain flaps: approx. 50 mm wide strips separated by slots ≥ 5mm.

Conclusion

Based on reducing spillage and clean-up labour, increasing equipment life and eliminating the need for dust collection, there is undoubtedly a return on investment for the control of fugitive dust with the right skirting and curtain designs. In the majority of cases such improvements also reduce respirable dust emissions, not only reinforcing the financial case but also justifying root-cause engineering solutions in the interests of health, safety and the environment.[2]

References

[1] Foundations, The Practical Resource for Cleaner, Safer, More Productive Dust & Material Control, Martin Engineering, 4th edition, copyright 2009.

[2] Foundations for Conveyor Safety, The Global Best Practices Resource for Safer Bulk Material Handling, 1st edition, copyright 2016.